This is the fourth in a series of class notes as I go through the free Udacity Computer Networking Basics course.

What is IP Addressing?

The “Internet Protocol” v4 address is a 32-bit number in “dotted quad” notation, for example 130.207.7.36. Each of the 4 numbers represent 8 bits, for a total of 32 bits. 8 bits of a binary number goes from 0 to 255 (remember that 2 ^ 8 = 256).

Therefore the total number of IPv4 addresses is 2^32, about 4 billion. Although we are running out of them, for our purposes here we will learn how to deal with all these addresses. If we were to store and look up each address individually, this would be expensive and inefficient.

So we group IP addresses up.

Pre 1994 Classful Addressing

Before 1994 we used “Classful” addressing, splitting IP addresses into “routing prefixes” (indicating class A B or C), “network ID” section and a “host ID” section:

There were only about 5000 Routing prefixes in Routing Tables back in 1992, but that accelerated in 1994 and it was clearly going to be unsustainable, and we began to run out of class C addresses, while still reserving entire chunks of IPv4 address space for unused A and B classes.

Classless Interdomain Routing (CIDR)

The classful strategy had failed to anticipate that demand would be huge for class C addresses and its inflexibility led us toward a new addressing protocol, CIDR. Instead of having fixed “network ID” and “host ID” portions of the 32 bits in IPv4, we would have an IP address with a “mask”, indicating the length of the network ID.

So 65.14.248.0/22 translates to a binary like this:

01000001 00001110 11111000 0000000

^^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^^^ ^^^^^^

first 22 bits are

network ID

So the “mask” is a variable length address prefix and independent of the range of IP addresses being used (whereas “classful addressing” basically fixed the address prefix lengths). This allows RIRs to allocate more flexibly according to size of the network.

However it is possible to have contiguous or overlapping address prefixes, e.g. both a 65.14.248.0/22 and a 65.14.248.0/24. In this case, 65.14.248.0/24 would be a subset of 65.14.248.0/22 (and more specific). If overlaps like these are found on a routing table, the solution is to forward based on the longest mask (aka address prefix) length. This “masking” of more specific addresses allow upstream routers (eg 65.14.248.0/8) to aggregate (and not announce) more specific prefixes.

CIDR was very successful in slowing the growth of routing tables to a linear rate from 1994 til the early 2000s. But from 2000 onward a new practice arose that made it difficult for upstream providers to aggregate IP prefixes together.

Multihoming vs IP Prefix Aggregation

Multihoming is when an AS (typically with a /24 mask) wants to be reachable via two upstream ISPs.

Let’s take an example with two ISPs, ISP1 and and ISP2. If ISP1 owns 12.0.0.0/8 and assigns 12.20.249.0/24 to our AS, our AS “multihomes” and advertises 12.20.249.0/24 to ISP2. Now both ISP1 and ISP2 want to advertise this prefix to the rest of the Internet. Although ISP1 might want to aggregate this prefix into 12.0.0.0/8, it can’t, because ISP2 is still advertising 12.20.249.0/24, and being a longer prefix, all the traffic would flow to ISP2. ISP1 is forced not to aggregate the AS’ prefix into the one it already owns.

So although CIDR aggregation was solving the growth in routing table size for a while, multihoming caused an explosion again because aggregation became less useful.

Address Lookups with Longest Prefix Match Algorithm

So CIDR requires LPM to look up the right prefix in a routing table efficiently, and LPM needs to search the space of all prefix lengths AND all prefixes of a given length. The other constraint is speed - an OC48 requires a 160 nanosecond lookup, or a max of 4 memory accesses.

Binary Tries are very speed inefficient, while Direct Tries or Exact Match strategies are space inefficient. We compromise by using “Multi-bit” or “Multi-ary” Tries. A k-ary Trie would then have Depth of W/K, Degree of 2^K, and Stride of K bits. Binary Tries are special cases of Multi-ary Tries where k=1, i.e. Depth is W, Degree is 2, and Stride is 1 bit. So we can control memory access by moving k to solve for the Depth that we want.

Further optimizations exist, like leaf-pushing, Luleå, and Patricia tries. Alternatives to Tries altogether also exist, for example Content-Addressable Memory lookups, which are basically exact-match.

Solutions to IPv4 exhaustion: Network Address Translation

NAT allows multiple networks to reuse the same private IP address space. Private IP addresses were reserved in 1996 (RFC 1918 where you can see the origin of familiar addresses like 192.168.0.0 and 172.16.0.0). NAT allows networks to reuse portions of internet address space, taking private IP addresses and translating to a single globally visible IP address. The NAT maintains a table mapping its public address and port to the private one that it rewrote.

This is popular for small/home office networks and VPNs. However, the End to End principle of the internet architecture is broken to do this.

Solutions to IPv4 exhaustion: IPv6 (128-bit addresses)

The other solution is IPv6. IPv6 not only adds a lot more bits for addresses, but clears up a lot of gunk in the header. Here’s a comparison of the required fields:

The benefits of IPv6:

- more addresses, of course

- simpler header

- easier multihoming

- built in security with IPSec/Extension Headers - (some caveats of course)

However, we have only seen very slow adoption of IPv6 so far, because IPv6 is hard to deploy incrementally. Everything runs on IPv4, with a massive network effect both above and below the narrow waist. Adopters face significant incompatibility issues. So far, Incremental Deployment involves either Dual Stacking IPv4 and IPv6 or Translation/Tunneling (kind of the same thing but with a separate layer just for 6 to 4 tunneling).

Aside: How IP Address Allocation works

IP addresses are allocated to ISPs by a hierarchy:

- At the top, the global Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) allocates to:

- one of five Regional Internet Registries: AfriNIC, APNic, ARIN, LACNIC, or RIPE. Which in turn allocates to:

- Individual ASes, like your university network

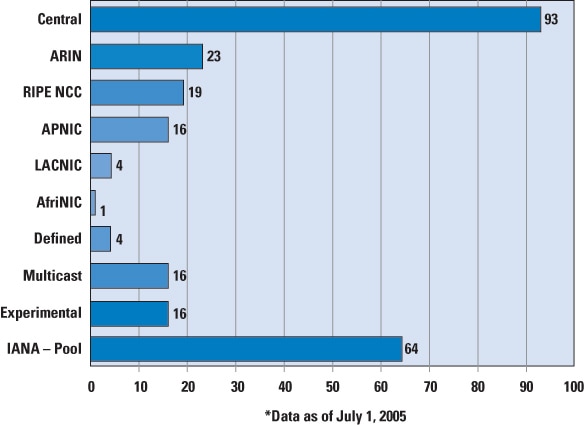

This worked until 2011 when IANA gave out the last “/8” block. Also fun knowledge, the allocations across registries aren’t even:

This is also a nice CIDR cheatsheet showing classful to classless translations as well as allocations in each address range and exceptions therein: https://oav.net/mirrors/cidr.html.

Next in our series

Hopefully this has been a good high level overview of why we need Switches and how they might work if we were to make our own Internet. I am planning more primers and would love your feedback and questions on:

- Architecture and Principles

- Switching

- Routing

- Naming/Addressing/Forwarding

- DNS

- Congestion Control and Streaming

- Rate Limiting and Traffic Shaping

- Content Distribution

- Software Defined Networks

- Traffic Engineering

- Network Security