Types or Tests: Why Not Both?

Every now and then, a debate flares up about the value-add of typed JavaScript. “Just write more tests!” yell some opponents. “Replace unit tests with types!” scream others. Both are right in some ways, and wrong in others. Twitter affords little room for nuance. But in the space of this article we can try to lay out a reasoned argument for how both can and should coexist.

Correctness: what we all really want

It’s best to start at the end. What we really want out of all this meta-engineering at the end is correctness. I don’t mean the strict theoretical computer science definition of it, but a more general adherence of program behavior to its specification: We have an idea of how our program ought to work in our heads, and the process of programming organizes bits and bytes to make that idea into reality. Because we aren’t always precise about what we want, and because we’d like to have confidence that our program didn’t break when we made a change, we write types and tests on top of the raw code we already have to write just to make things work in the first place.

So if we accept that correctness is what we want, and types and tests are just automated ways to get there, it would be great to have a visual model of how types and tests help us achieve correctness, and therefore understand where they overlap and where they complement each other.

A visual model of Program Correctness

If we imagine the entire infinite Turing-complete possible space of everything programs can ever possibly do, inclusive of failures, as a vast gray expanse, then what we want our program to do, our specification, is a very, very, very small subset of that possible space (the green diamond below, exaggerated in size for sake of showing something):

Our job in programming is to wrangle our program as close to the specification as possible (we are imperfect, and our spec is constantly in motion, e.g. due to human error, new features or underspecified behavior, so we never quite manage to achieve exact overlap):

Note, again, that the boundaries of our program’s behavior also include planned and unplanned errors, for the purposes of our discussion here. Our meaning of “correctness” include planned errors too, while unplanned errors are not in our specification and therefore take us further away from correctness.

Tests and Correctness

We write tests to ensure that our program fits our expectations, but have a number of choices of things to test:

The ideal tests are the orange dots in the diagram - they accurately test that our program does overlap the spec. In this visualization we don’t really distinguish between types of tests, but you might imagine unit tests as really small dots, while integration/end to end tests are much larger dots. Either way, they are dots, because no one test fully describes every path through a program. (In fact, you can have 100% code coverage and still not test every path because of the combinatorial explosion!)

The blue dot in this diagram is a bad test - it tests that our program works, but doesn’t actually pin it to the underlying spec (what we really want out of our program, at the end of the day). The moment we fix our program to align closer to spec, this test breaks, giving us a false positive.

The purple dot is a valuable test - it tests how we think our program should work, and identifies an area where our program currently doesn’t. Leading with purple tests and fixing the program implementation accordingly is also known as Test-Driven Development.

The red test in this diagram is a rare test - instead of normal (orange) tests, which test “happy paths” (including planned-for error states), this is a test that expects and verifies that “unhappy paths” fail. If this test “passes” where it should “fail”, that is a huge early warning sign that something went wrong, but it is basically impossible to write enough tests to cover the vast expanse of possible unhappy paths that exist outside of the green spec area. People rarely test like this, so they don’t do it, but it can still be a helpful early warning sign when things go wrong.

Types and Correctness

Where tests are single points on the possibility space of what your program can do, types represent categories - carving entire sections from the total possible space. We can visualize them as rectangles:

We pick a rectangle to contrast with the diamond representing the program, because no type system alone can fully describe your program behavior using types alone. (To pick a trivial example of this, an id that should always be a positive integer is a number type, but the number type also accepts fractions and negative numbers. There is no way to restrict a number type to a specific range, beyond a very simple union of number literals.)

Types serve as a constraint on where your program can go as you code. If your program starts to exceed the specified boundaries of your program’s types, your typechecker (like TypeScript or Flow) will simply refuse to let you compile your program. This is nice, because in a dynamic language like JavaScript, it is very easy to accidentally create a crashing program that certainly wasn’t something you intended. The simplest value add is in automated null checking - If foo has no method called bar, then calling foo.bar() will cause the all too familiar undefined is not a function runtime exception. If foo were typed at all, this could have been caught by the typechecker while writing, with specific attribution to the problematic line of code (with autocomplete as a concomitant benefit). This is something tests simply cannot do.

So we might want to write strict types for our program as though we are trying to write the smallest possible rectangle that still fits our spec. However, this has a learning curve, because taking full advantage of type systems involves learning a whole new syntax and grammar of operators and generic type logic needed to model the full dynamic range of JavaScript.

Fortunately, this adoption/learning curve doesn’t have to stop us. Since typechecking is an opt-in process with Flow and of configurable strictness with TypeScript, with the ability to selectively ignore troublesome lines of code, we have our pick from a spectrum of type safety. We can even model this too:

Larger rectangles, like the big red one in the chart above, represent a very permissive adoption of a type system on your codebase, for example allowing implicitAny and fully relying on type inference to merely restrict our program from the worst of our coding.

Moderate strictness (like the medium size green rectangle) could represent a more faithful typing, but with plenty of escape hatches like using explicit any’s all over the codebase and manual type assertions. Still, the possible surface area of valid programs that don’t match our spec is massively reduced even with this light typing work.

Maximum strictness, like the purple rectangle, keep so tight to our spec that sometimes it finds parts of our program that don’t fit (often these are unplanned errors in our program behavior). Finding bugs in an existing program like this is a very common story from teams converting vanilla JS codebases. However, getting maximum type safety out of our typechecker likely involves taking advantage of generic types and special operators designed to refine and narrow the possible space of types for each variable and function.

Notice that we don’t technically have to write our program first before writing the types. After all, we just want our types to closely model our spec, so really we can write our types first and then backfill the implementation later. In theory this would be Type Driven Development; in practice, few people actually develop this way since types intimately permeate and interleave with our actual program code.

Putting them together

What we are eventually building up to is an intuitive visualization of how both types and tests complement each other in guaranteeing your program’s correctness.

Your Tests assert that your program specifically performs as intended in select key paths (although there are certain other variations of tests as discussed above, the vast majority of tests do this). In the language of the visualization we have developed, they “pin” the dark green diamond of your program to the light green diamond of your spec. Any movement away by your program breaks these tests, which makes them squawk. This is excellent! Tests are also infinitely flexible and configurable for the most custom of use cases.

Your Types assert that your program doesn’t run away from you by disallowing possible failure modes beyond a boundary that you draw, hopefully as tightly as possible around your spec. In the language of our visualization, they “contain” the possible drift of our program away from our spec (as we are always imperfect, and every mistake we make adds additional failure behavior to our program). Types are also blunt, but powerful (because of type inference and editor tooling) tools that benefit from a strong community supplying types you don’t have to write from scratch.

In short:

- Tests are best at ensuring happy paths work

- Types are best at preventing unhappy paths from existing

Use them together based on their strengths, for best results!

— unused draft text—

A Philosophy of Testing

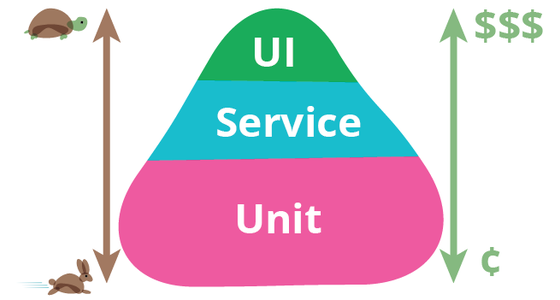

When we talk about testing in JavaScript, we often refer to a range of testing techniques varying in fidelity and speed, typically characterized by some form of pyramid:

Some folks have different names for each of the layers, like Integration tests, End to end tests, and Manual or Acceptance tests but ultimately the basic idea is that you can test the same lines of code multiple different ways, and you should do some more than others. Unit tests are faster and more specific, so if some functionality breaks, they are likely to point you to exactly where things are going wrong with a short feedback loop. This is very nice to have, however the specificity comes at the cost of relying on more implementation details that are likely to change (at its worst, this often leads to double work between maintaining code and updating tests of that code).

At the other end of the spectrum, testing hews closer to how users experience your app (which is far more robust to leaking implementation detail), and can ensure more dependencies (including backend dependencies) of your app are tested, but this is a much slower, more expensive, and often imprecise process. It can sometimes be unclear if the benefits are worth the cost, and many

As you can see, testing is a nuanced topic that adds additional engineering overhead on top of actually getting things done - so much so that many forgo testing altogether to skip the decision fatigue, or at the other extreme, adopt the absolutist attitude that 100% test coverage is an actual ideal worth striving for. This is why Guillermo Rauch and Kent C. Dodds have been leading a movement for a “fat middle” form of the pyramid to preserve the best of the benefits of testing against the costs: “Write tests. Not too many. Mostly integration.”

JavaScript has a wealth of tooling addressing different aspects of